Recently, a woman came into the State Archives with a very old, very large document. It was folded parchment paper covered in beautiful scrolling letters. She said she bought it years ago at a garage sale somewhere in the state, and she brought it in to see what, if anything, we could tell her about it. Specifically, she wanted to know if we could help decipher the handwriting to tell her what it was and who was involved.

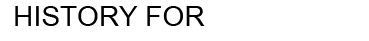

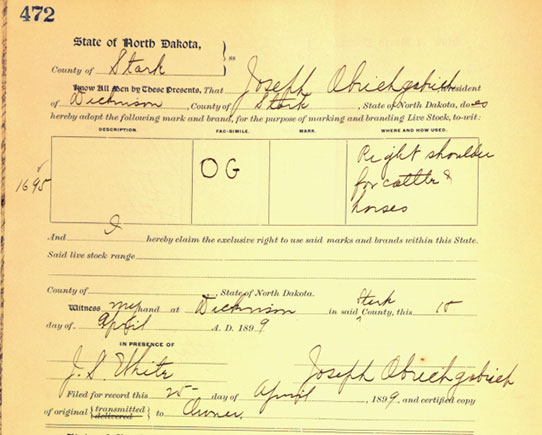

This document is from a brand registration book. Partially hand-written, partially print, the image of the chosen brand was inked into the box.

The Archives holds many partially and fully hand-written documents.[i] Since it is our goal to maintain these records and make them accessible, we often have to index and transcribe them. Unfortunately, that old script and handwriting is not easy for our modern eyes to read. In the instance of this old document, the writing was clear (not always true in these records), but it was flourishing and calligraphic, and not spaced in any way like the text you are reading on this screen.

Handwriting may range from scratch marks to grandiose flourishes, but script type is not the only reason these types of records are hard to read. For example, some authors and originators of these records had limited communication and education. The clerks recording these documents (who would have had some formal education) might have been dealing with individuals who didn’t speak English, much less write in it.

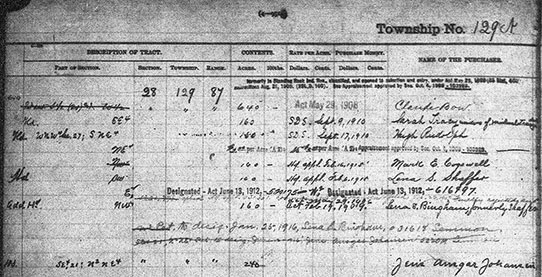

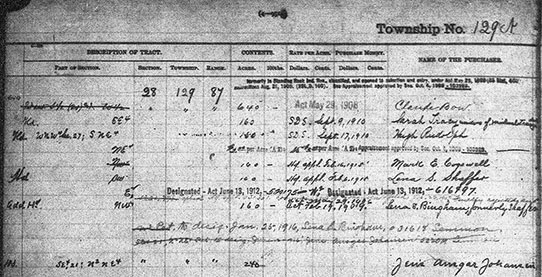

This is a selection from a tract book record, showing some of the first purchases of land. Handwriting is not the only issue in these sorts of records; different codes indicated different things, different types of ink are used in the record (difficult to tell here, as this is taken from the microfilmed copy), and often, different handwriting can be seen on the same pages.

Even though the majority of settlers here spoke languages derived from the same Proto-Indo-European language base,[ii] the languages were spoken differently, accented differently, and sometimes were written differently. [iii]). Recording what was heard, trying to determine how it was spelled, and gaining some semblance of accuracy must have been difficult enough.

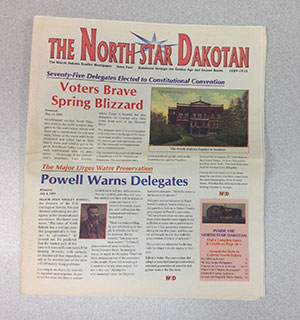

Some clerks or other individuals ended up using their native tongue in documents, or used a mixture of languages in these documents. However, even some typed items show obvious differences, such as old German script, as seen in this German-published Staats-Anzeiger newspaper from 1907.

Der Staats-Anzeiger was published in different locations in North Dakota at different periods of time. Entirely in German, it used old German typescript. These papers often published local items of interest, such as letters to and from the old country and other parts of the new country from German settlers in the area.

This image is one of many in our collections that contain some identifying information on the back of the picture. The image is below. To the best my eye can see, the text reads: “On Capitol grounds- Mac (arrow up points to Mrs. A. E. McLean Kenmare asst.) and me – soliciting funds for Indians girls’ trip to Dinner. June 1 – 1930 To secure $600.00 (Later – I got it – girls and staff went)”

More frequently than not, we in the Archives receive or discover these items when both parties are long gone. By this time, we are also dealing with old records that may have been housed in poor conditions, resulting in the added possibility of deterioration.

So, how do we determine what is on these records?

Everything is a clue. We know some script types are different, and we know when (and in what language) they are more prevalent. We know older and earlier records mean certain things.[iv]

Sometimes we can also figure it out by looking at other handwriting on the pages. For example, if I can determine a few words, I can then match some letters in other words, and perhaps find a few more, until I can eventually understand the gist of what is being said. I then know what the letters of those words should look like, and may be able to determine a few more words. We can draw a very pale comparison to the significance of the Rosetta stone, and how linguists were able to determine a fully different language through the use of words they already knew.[v] And of course, it helps to have images to pair with names, newspapers to check for ongoing events, and even a general idea of the area. It also helps to know who might have been in the area. Catholics might have used Latin in some of their documents. If Scandinavians settled more in one area than another, we might be able to guess (if we don’t know) that an item from that area is written in Norwegian, rather than Ukrainian.

As for that old, fully hand-written document that I mentioned at the beginning; the woman was able to pick out a few words, and we figured out a few more, so we did help her somewhat. We were able to help her determine that it was an indentureship agreement from the east coast.[vi]

Reading old writing can be tough, but it is thrilling to determine one more piece of the puzzle.

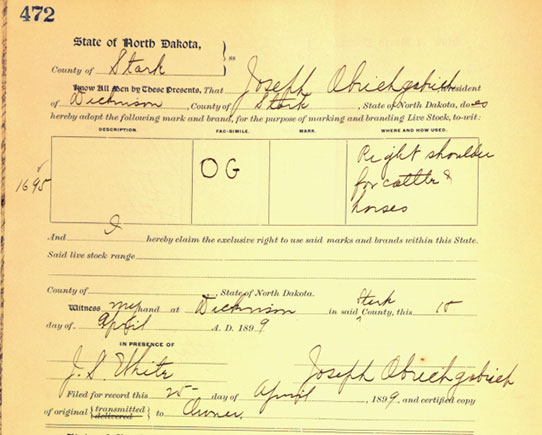

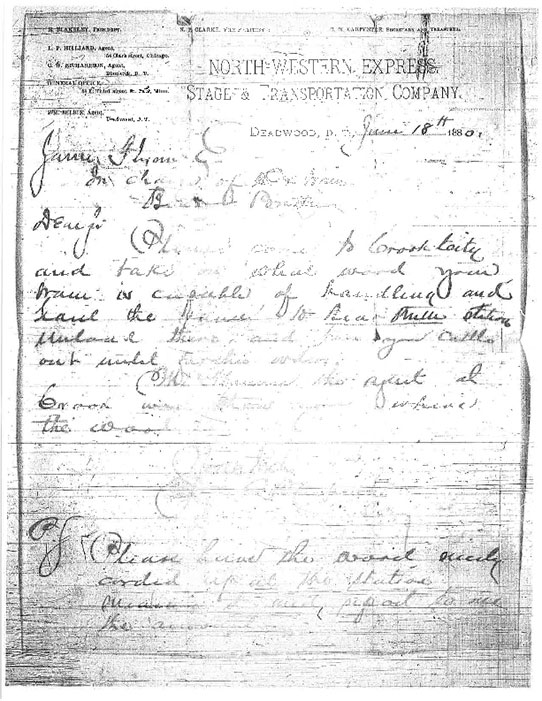

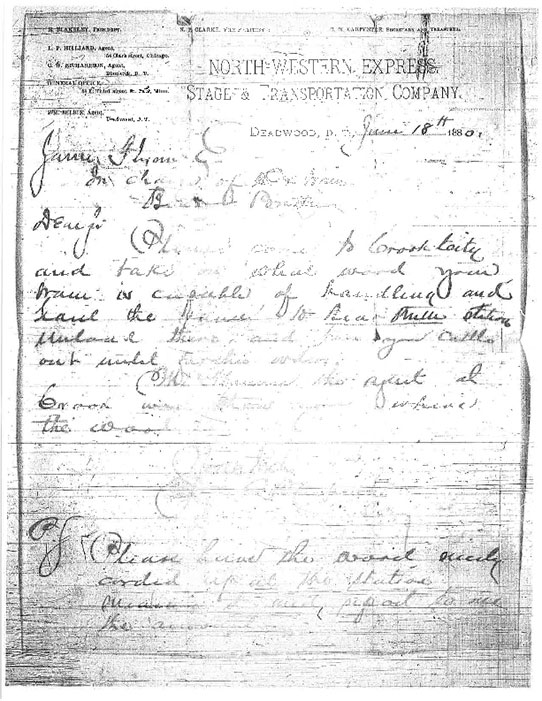

This page is taken from the pages of MSS 10369, James Flynn’s papers, 1878-1887. This collection consists of receipts, financial accounts, and correspondence concerning the distribution of grain and supplies and the transfer of cattle by a wagon master of the North Western Express, Stage, and Transportation Company. Again, this is from microfilm, and the copy is already in poor condition. What can you make out?

[i] There are several types of records, actually. Some predate handwriting. (I’m thinking of the gorgeous winter counts on display in our museum in the Early Peoples/Innovation gallery.) Then some are electronic. We will save discussion about these other records for another day.

[ii] I am not an expert in linguistics—more of an enthusiast—but suffice it to say that many/most languages are linked, and more than just through derivation from Latin, Greek, Old German, Old French, Old English…etc. This looks like a good site if you want more information about PIE.

[iii] If you go back early enough, different peoples used a completely different system of writing. Have you ever heard of the ancient Sumerians? Cuneiform, their system of writing, is the earliest known writing system. It mostly looks like lines, squares, squares with lines through them, etc. Then there are pictographs, hieroglyphs, and images such as those found at Writing Rock State Historic Site.

[iv] In North Dakota, this may mean fewer type-written records, and more script from the old countries.

[v] I went to England in 2013, and while there, went to the British Museum for one day (fast trip). Seeing the Rosetta Stone was almost mind-blowing and life-altering for me. If you’re interested in finding out more on the stone, this looks like an interesting read.

[vi] Basically, the named parties would be servants to one man for a number of years, serving for him until they had paid off their debts (apparently for passage to America). The second page, I believe, released the family from this debt, after time was served. The document was from the 1700s/1800s.