How Do You Move A Car With Four Flats and No Gas Halfway Across Town Without Killing Anyone?

As the assistant curator of collections, I care for our state’s amazing history and natural history collections. I work with artifacts such as quilts, (thankfully disarmed) bombs, taxidermy, moon rocks, and any number of items in a given week. With a collection of nearly 70,000 artifacts, I see something that surprises me at least once a week.

Since October, one of my primary jobs has been to prepare collection artifacts before they go into the new galleries. But what goes into preparing the artifacts for those exhibits? I’d like to take you behind the scenes and show you just how much care went into one artifact you will see in the Inspiration Gallery this fall.

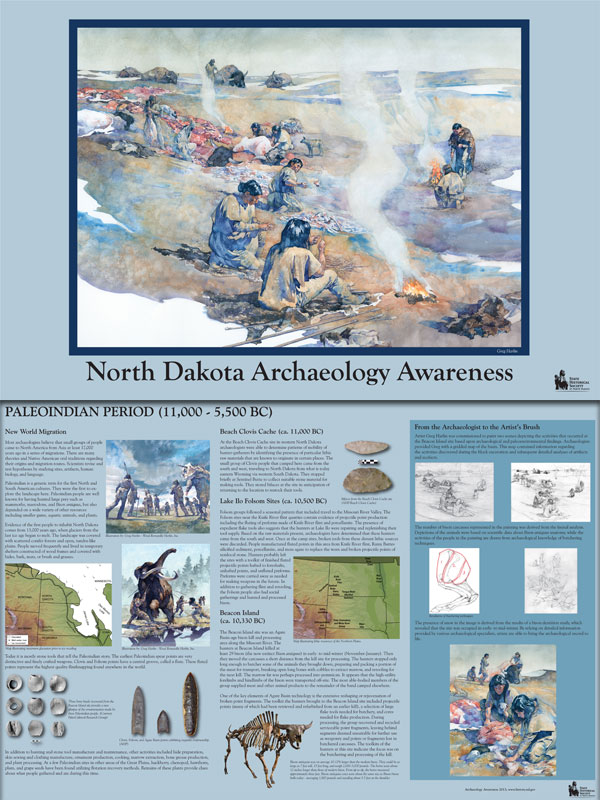

This 1929 Erskine Cabriolet, originally owned by a North Dakota woman, was bought for the Historical Society’s collection in 1955 with 30,000 miles on the odometer. It is currently installed in the museum’s Inspiration Gallery, which is opening to the public on November 2, 2014.

This 1929 Erskine Cabriolet requires a bit more care than most artifacts due its size. First, the staff assessed its condition and wrote a formal condition report to record the condition it was in before we put it on display. The report provides a baseline to identify any damage that occurs while the artifact is in the gallery. At that time it was decided the car needed to be cleaned, both so it looked nice for the exhibit and to identify any preservation issues that needed to be addressed. Our goal is to ensure that the artifacts in our care are around for as long as possible, and it’s a duty we take very seriously. Being a collection item, we couldn’t just run the Erskine through a touch-free car wash, so we had to use a gentler technique to get it ready for exhibit.

To remove dust from the exterior, we dipped rags in water, rang them out until they were slightly damp, and then gently patted the vehicle. While it is time consuming, patting (rather than scrubbing) prevents scratches to the finish and minimizes the risk of removing paint.

Before it could go on display, the Erskine needed a thorough cleaning. In this image, Curator of Collections Management Jenny Yearous and Intern Stephanie Templin dab the exterior with damp rags to remove dust. On the passenger side of the windshield, you can see a sticker with the letter “A”. It is a World War II gas ration sticker, which permitted the owner to buy up to four gallons of gas per week.

The interior of the vehicle is leatherette, cloth, wood, and unfinished metal, materials that don’t always react well to water. Instead of using damp rags, we vacuumed the interior to remove dust and debris while checking for signs of pests. That was repeated for the engine compartment and the rumble seat in the back.

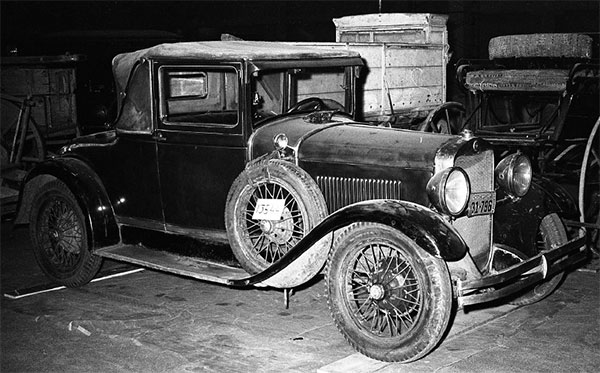

Once it was clean, we needed to figure out how we were going to get it from our off-site storage facility back to the Heritage Center. We would never drive the Erskine, and even if we wanted to, none of the tires hold air anymore due to their age. We decided to contract with a moving company and use a tilt bed trailer to transport the car.; It was rolled onto the truck, then driven to the Heritage Center.

Moving day. A cable was attached to the car and a winch was used to pull the Erskine up onto the tilt bed. It was then secured to the trailer bed and driven to the museum.

Chief Preparator Bryan Turnbow thinks about the best way to get the car inside. If you look closely you can see how it was secured to the trailer, by tying it down at strong points of the frame and body. We didn’t want it rolling off the back or tipping during transport.

Once here, a wheeled jack was placed under each tire. Using a strap, the Erskine was pulled into the gallery by a forklift.

To get the car inside, wheeled jacks were placed under each tire and a strap was attached to a point on the rear end. On the right side of the image, you can see the forklift that was then used to pull the Erskine inside. Another staff member and I were at the front, pushing on the fenders and hood to help steer the vehicle. It was a relief when it was finally in place with no damage.

Here, you can see the Erskine in its final location in the partially completed Inspiration Gallery. Come see it at the grand opening on November 2nd!

The Erskine is one of 956 artifacts that are going into the Inspiration Gallery. It required a bit more care than most, but I hope it gives you an idea of just how much went into everything you see in our exhibits. Join us at our grand opening on November 2 to see the Erskine and much more!